In a country where bullets often speak louder than ballots, what does it mean for a Church leader to stand for peace without being swallowed by politics?

Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis has now stretched for nearly a decade. Villages burned, schools shut, families scattered across borders; an entire generation of young people is growing up knowing more about checkpoints and kidnapping than about libraries and laboratories. In this landscape, religious leaders are not a side-show. They are sometimes the last remaining institutions people still trust.

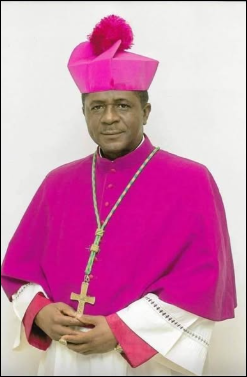

At the centre of this moral terrain stands Archbishop Andrew Fuanya Nkea – born in Widikum with Bangwa roots, educated in Anglophone seminaries, now Archbishop of Bamenda and President of the National Episcopal Conference of Cameroon (NECC). His voice does not echo from a safe distance; his home regions have been among the hardest hit by the violence, and he has walked through burned villages and refugee camps to see the damage for himself.

Over the years, Archbishop Nkea has come to symbolise a particular style of African religious leadership: non-violent, dialogical, committed to the dignity of ordinary people – yet constantly accused, from different sides, of not going far enough.

This editorial takes a step back from the noise to ask: What exactly is Nkea doing – and what does his posture say about the future of faith-based leadership in African conflicts?

A Bishop in the Crossfire

From the beginning of the Anglophone protests in 2016, Nkea’s public message has been remarkably consistent on one central point: this crisis will not be solved by the gun. Whether speaking as Bishop of Mamfe or later as Archbishop of Bamenda, he has refused to bless a military “solution” and has instead pushed for “genuine dialogue” between the state and separatist leaders.

That commitment to dialogue is not abstract theology. It grows out of his pastoral encounters: parents too frightened to send their children to school, traders paying multiple “taxes” to survive, priests kidnapped in the line of duty, and villages razed during security operations. His homilies and interviews circle back, again and again, to the same triad: reject war, protect civilians, open channels for meaningful talks.

But Nkea is not only a bishop of a suffering region; he is also President of the NECC. That national role has drawn him into the broader political conversation beyond the Anglophone conflict – especially around elections. Ahead of the 2025 presidential poll, he urged Cameroonians to register massively, to vote peacefully, and to contest results through legal institutions rather than through street violence. In a country where abstention, cynicism and apathy are increasingly tempting options, that insistence on participation is itself a moral stance.

In short, Archbishop Nkea has tried to inhabit a double identity: pastor of a wounded people in the North-West and South-West, and national moral voice calling all citizens – Anglophone and Francophone alike – away from despair and towards engagement.

The Uneasy Art of Naming Violence

Yet it is precisely at this intersection of roles that the criticisms sharpen.

Many Anglophone activists and sympathisers accuse Nkea and other bishops of being too close to the state. They point to their participation in the 2019 Major National Dialogue – widely seen by critics as too controlled from Yaoundé – and argue that simply showing up lent legitimacy to a process that did not include key separatist voices or address fundamental grievances.

Others highlight a different asymmetry: Church leaders often call out separatist abuses explicitly – kidnapping of priests, attacks on schools, extortion at roadblocks – while speaking of state violence in more generic terms: “excesses,” “security operations,” “violence affecting civilians.” In a context where many people experience the brunt of the conflict at the hands of state forces, this softer language can feel like silence.

There are, however, reasons why a bishop might choose his words carefully. In Cameroon, religious leaders who cross certain red lines do not only receive angry tweets; they may receive court summons or administrative harassment. In 2017, several Anglophone bishops and Protestant leaders were dragged before a court, accused of “paralysing schools” and threatening national unity. More recently, tough rhetoric from central government about “unruly NGOs” and “unregulated churches” has reminded everyone how quickly legal tools can be weaponised against religious and civil-society actors.

In such an environment, cautious language can be a shield – not only for the Church as an institution, but for vulnerable communities on the ground. Diplomacy, however, comes at a cost: those most exposed to state abuses may feel abandoned when their suffering is not named with the same precision as other crimes.

“Hard on One’s Own”: Anglophone, Pastor, Critic

There is also another, more intimate layer to Nkea’s stance that deserves attention.

Archbishop Nkea is not a neutral outsider to the Anglophone story. He is an Anglophone whose own communities have paid dearly in this conflict. When he speaks sharply against kidnappings, forced school boycotts, and attacks on clergy and traders, he is not simply “protecting the regime”; he is scolding “his own sons” – young men he believes have taken a just cause and disfigured it with unacceptable means.

This pattern – being toughest on one’s own side – is not unique to Cameroon. Irish bishops in Northern Ireland often used their harshest words for IRA bombings, even while criticising British policies more carefully. In South Africa, Desmond Tutu insisted the Truth and Reconciliation Commission expose not only apartheid crimes but also abuses by liberation movements he personally admired. In the Central African Republic, Christian and Muslim leaders publicly rebuked militias drawn from their own religious communities, explicitly separating their faiths from the atrocities committed in their name.

Seen in that broader African and global perspective, Nkea’s discourse looks less like a simple tilt towards the state and more like a deliberate, if risky, strategy: hold “our own” accountable in public while trying – mostly through quieter channels – to move the state towards reform.

Whether that balance is working is precisely what is up for debate.

Not Alone: A Wider African Pattern

It is tempting to treat every conflict and every religious leader as an isolated case. Yet when we compare Archbishop Nkea to other prominent figures across the continent, a pattern emerges.

In Cameroon itself, the late Cardinal Christian Tumi refused both separatist and state violence, pushing instead for an All Anglophone General Conference where people could debate their future peacefully. Protestant leaders like the Moderator of the Presbyterian Church in Cameroon and the head of the Cameroon Baptist Convention have repeatedly insisted that “the barrel of the gun cannot resolve the ongoing conflict,” calling for ceasefires and negotiations. Muslim leaders in Buea and Bamenda have joined them in joint statements urging both the army and armed groups to put down weapons.

In Nigeria, Archbishop Ignatius Kaigama, Bishop Matthew Kukah and Cardinal John Onaiyekan have long combined criticism of corruption and structural injustice with hands-on peacebuilding and election monitoring. In Congo, Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo speaks forcefully against both rebel predation and government failures. In the Central African Republic and South Sudan, interfaith platforms and “peace villages” have tried to embody reconciliation on the ground.

Across these stories, the same ingredients recur: rejection of war as a solution, protection of civilians, defence of political participation, and willingness to sit at difficult tables with governments, rebels, and communities. Nkea’s style fits this wider tradition of African religious engagement in conflict – neither revolutionary nor regime propaganda, but something more complex and, often, more fragile.

Catholic Social Teaching: A Quiet Compass

Underneath the politics runs a deeper question: Is Archbishop Nkea faithful to the moral tradition his Church claims to teach?

Catholic Social Teaching (CST) is not an abstract library of Vatican documents; it is supposed to be a compass for real-world choices. On that terrain, Nkea’s stance lines up with several core principles:

- Human dignity and the sanctity of life: his repeated focus on civilians, refugees and displaced families.

- Preferential option for the poor and vulnerable: his concern for communities living under both military and separatist pressure.

- Peace as the fruit of justice and charity: his insistence that reconciliation must address real grievances, not simply call for “calm.”

- Political participation and the common good: his strong encouragement of voter registration and peaceful, law-based contestation of election results.

- The Church as neither party nor spectator: his effort to engage state processes without becoming their chaplain.

The tensions arise not from doctrine but from prudence: how loudly should a bishop denounce specific state abuses? How close can he come to government initiatives without being co-opted? CST does not give mechanical answers to those questions. It demands that injustice be named, yes – but it also recognises the need for pastoral judgment in environments where one wrong word can close doors that communities desperately need left open.

Why This Matters Beyond Cameroon

Why should readers across Africa and the diaspora pay attention to the fine-grained choices of one Cameroonian archbishop?

Because the dilemmas he faces are not uniquely Cameroonian. They are African dilemmas. They will recur wherever elections are fragile, security forces are mistrusted, and armed groups claim to speak for the marginalized.

In such contexts, our religious leaders will always be pulled in opposite directions. If they refuse to sit with governments, they risk irrelevance. If they sit too comfortably, they risk capture. If they speak too softly, the oppressed feel abandoned. If they speak too loudly, the vulnerable may pay the price.

Archbishop Andrew Nkea is walking that tightrope in real time. One may disagree with his emphasis, his tone, or his strategic choices. One may wish he had named state abuses more directly or engaged less with state-organized dialogues. Those debates are legitimate – and necessary.

But if we reduce him, or any similar leader, to a simplistic label – “regime ally” or “heroic resistor” – we miss the bigger story: the story of how African religious leadership is being reinvented under fire.

For African Excellence Magazine, this is where the challenge lies. Excellence, in this case, is not perfection. It is the hard, imperfect work of holding peace and justice together; of being prophetic without becoming reckless, and prudent without becoming cowardly.

Archbishop Nkea has not solved Cameroon’s crisis. No single leader can. But his journey – with its courage, its ambiguities, and its missteps – offers a mirror to all of us who expect our faith leaders to “speak truth to power” while also helping hold fractured societies together.

The question is not only what we demand of him. It is also what kind of moral leadership we are ready to support, protect, and listen to when the next crisis comes – whether in Cameroon or elsewhere on our continent.